Well, 2020 is finally coming to a close. What a year! There’s no point lamenting the bleak state of current affairs, which is of course not set to miraculously improve for most once the calendar turns over in a few days. There are plenty of other outlets better suited for that, and seeing as this column is essentially devoted to escaping the soul crushing reality of modern existence via appreciation for all manner of ill-advised behavior committed to tape, we can at least count our lucky stars that there was plenty of time to bask in the rays of such artifacts from the comfort of one’s own hovel over the course of this latest jaunt ’round the sun. I don’t really have a “Top Releases of the Year” or anything in mind, but rather a few desultory musings on things that kept me afloat ~*aesthetic life rafts if you will*~ in the turbulent existential waters of 2020, Year of Our Lord:

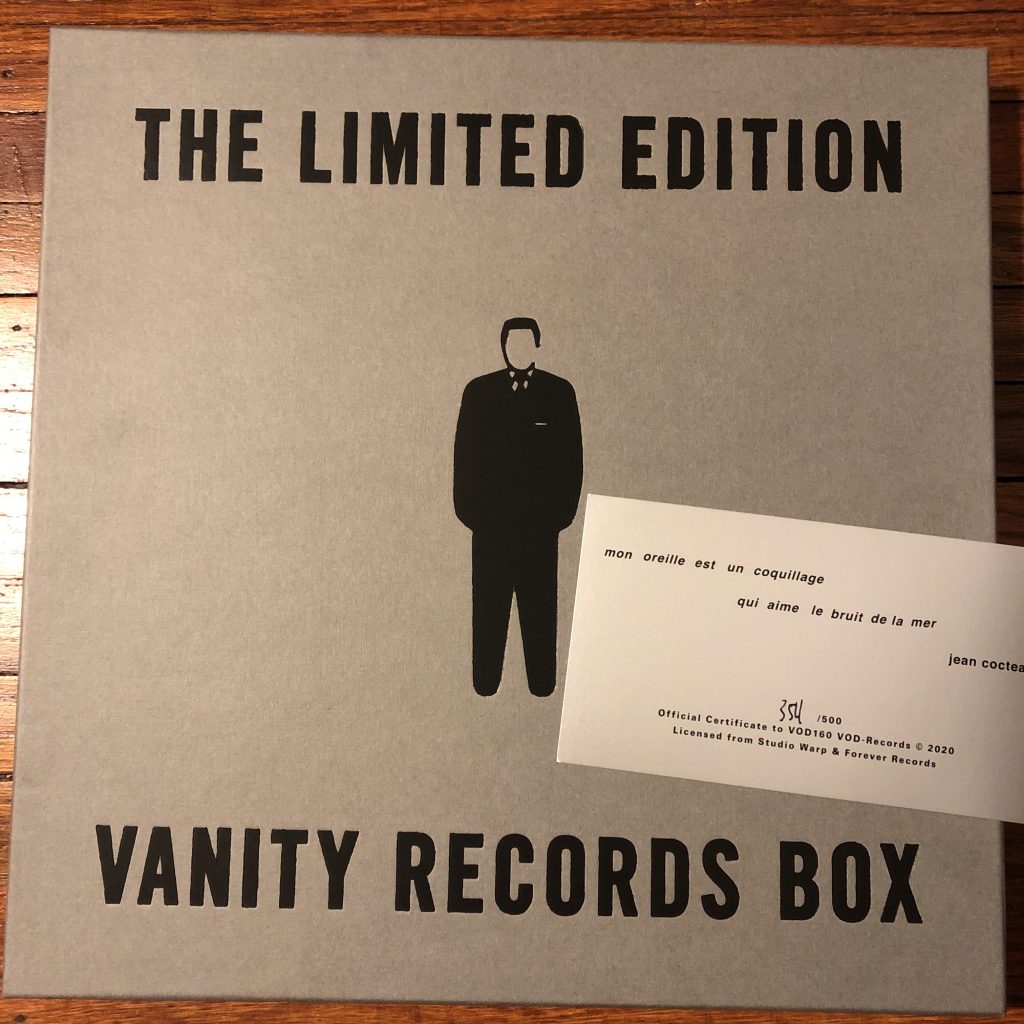

Vanity Records has of course been lauded by ‘heads’ far and wide for a long time now. Strangely enough, however, the back catalog has been poorly served by official reissue campaigns until recently. This was reportedly due to an ambitious project headed by label owner Yuzuru Agi (who remained involved in all kinds of music/design-related activity following Vanity’s shuttering in 1982), that was to collect the label’s entire output in expansive, remodeled packaging. Sadly this never came to be during Agi’s life, as he passed away in late 2018. I’m not sure what the circumstances were following his death and am certainly not suggesting impropriety on anyone’s part, but shortly thereafter some seemingly haphazard reissues started trickling out. Then early this year the flood gates finally opened, as multiple retrospectives were announced (Unreleased demos! A third Tolerance full length!), but again, if Discogs comments are to be believed (second only to YouTube in terms of journalistic integrity), their quality was a source of dispute.

I sat on the fence for a while, wary of getting burnt by a substandard presentation of this seminal material, and was glad to see that the release I’d most anticipated, the Limited Edition… cassette box (aka “Working On A Plan”), was to receive LP pressing from the trustworthy Vinyl On Demand. While I have no OG tapes with which to compare, the audio seems excellent to me, and the fairly bare bones packaging, with original CS artwork printed on 12″ sleeves, does the job just fine. I’ve always maintained that, next to the Tolerance LPs/flexi and Music comp (also done by VOD), “Working On A Plan” was the label’s peak. The recordings for both the tapes and Music were reportedly selected out of hundreds of demos sent to the label, and feature some of the strangest, most subterranean sound of the era. The boxset material in particular is just so queasy and off-kilter, with an abstruse, hermetic vision the whole way through. It’s remarkable that they came from different artists given their peculiar sonic similarities, more akin to six iterations of a particular group of like-minded amateur musicians. Then again, along with the likes of early Tori Kudo-fronted vehicle Noise, Unbalance records etc. there was clearly something in the water around Osaka at the time. And, joy to all, those previously unreleased/demo boxsets are scheduled for the VOD treatment early ’21 as well, so there’s something to look forward to next year in spite of all the doom/gloom. If that’s not worthy a Denki Noise Dance I don’t know what is!

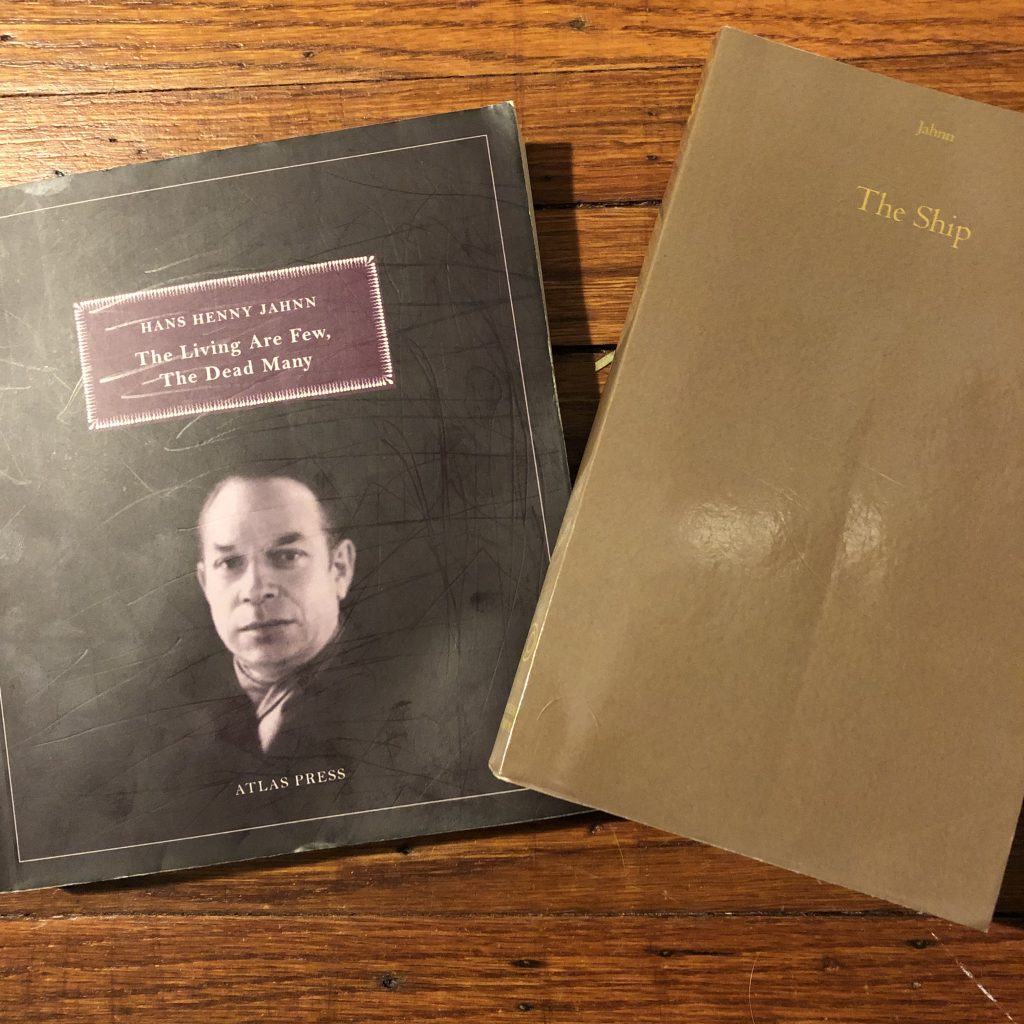

Of course, listening to music is but one of a multitude of activities a person can undertake within the confines of quarantine. All kinds of things are done between four walls, and establishing a sense of equilibrium is crucial during such trying times. I endeavored, with some success, to read more given the uncharacteristic surplus of free time. Much of this reading concerned fairly meat ‘n potatoes organized labor history/strategy (and, a little later in the year, parenting books), but I did make plenty of room for less practical matters as well. The best new (to me) author I came across was undoubtedly Hans Henny Jahnn, whose incredible work was recommended by my friend Stew Skinner. Jahnn’s fiction, written from around the end of the first World War until his death in 1959, is strikingly relatable today in its roily, ambient horror (Stew always has an acute sense of timing for such things).

There’s a telling anecdote in the introduction to the short story collection The Living Are Few, The Dead Are Many about an embellished autobiographical detail concerning forced visits to the gravesite of his older brother, who Jahnn claimed shared his exact name and died before he was born (thus the young Hans felt as if he had been shown his own grave), an event he described as “…one of the most appalling, truly satanic impressions I had to deal with as a child.” A preoccupation with death, or rather the impossibility of a clean break from this wretched existence into nothingness, is a fixture of Jahnn’s writing, which, despite its often dour subject matter, is frequently punctuated by the sort of pitch black humor one finds in an Otto Dix painting. Comparisons have been drawn to such contemporaries as Broch, Döblin and Joyce, but there is something uniquely unsettling about all aspects of the environs Jahnn conveys, fascinating and unflinching compendiums of the myriad ways lives go wrong. In addition to writing plays and fiction, Jahnn, obsessed with the concept of harmonics, was renowned in the fields of organ-restoration, burial architecture and environmentally-conscious crop hormone research, though he had trouble publishing much of anything while in exile from his native Germany during the second World War. I can’t think of a fiction writer who’s impacted me more since I first came across Samuel Delaney.

Speaking of recommendations, the new-to-me thing I listened to most all year was probably a record suggested by my friend Steve White, that being Byard Lancaster It’s Not Up To Us (Vortex, 1968). Early in the summer, I was growing exhausted with much of what I typically turn to for psychic relief, so I hit up Steve, a wealth of knowledge in many areas of music I know fuck all about. He mentioned a lot of great stuff, but this early session headed by “Philly Sax” legend Lancaster, featuring Jerome Hunter, Eric Gravatt, Keno Speller and Sonny Sharrock proved especially potent. I’m clueless when it comes to writing about jazz as is, but this record has a real sum-greater-than-its-parts quality that defies description, proto-‘spiritual’ vibes amid an understated, brooding atmosphere, at times dark and intense but also uplifting and completely engrossing. Being stuck at home, I spent more time with my actual collection, so often neglected, than I can possibly ever recall, rarely listening to more than a clip of anything I didn’t own. Unfortunately, I still haven’t picked this up (it’s a somewhat tough pull in decent condition), but along with the two Judee Sill LPs (who, although obviously sounding nothing like Lancaster, has a similarly idiosyncratic set of signifiers that transcends genre), It’s Not Up To Us notched plenty of YouTube counts throughout the year. Follow it up with Sharrock’s Black Woman (also on Vortex) for maximum brain wash.

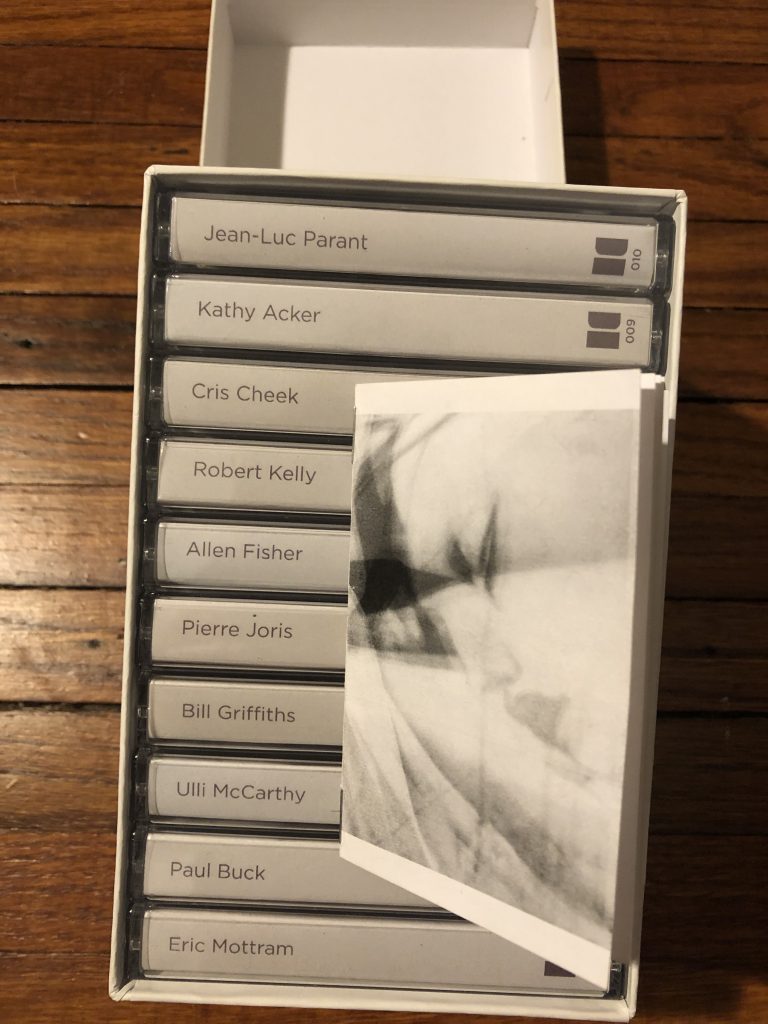

As stated, much Quality Time in 2020 was spent with the reams of audio I’ve accumulated on physical formats over the years. Things that were played once and filed away were finally given a fair hearing, I made it past the fifth side of all those boxsets that take up so much shelf space (in many cases for the first time ever) and so on. I didn’t even bother with many new acquisitions, as it seemed more interesting to rediscover what I already had lying around (dig in my own crates, if you will). One semi-recent release that got a proper airing out was Paul Buck’s Pressed Curtains Tape Project (Test Centre/Blank Editions, 2015). I recall being pretty excited upon its initial release and giving it a few rounds, but finding the time and attention for 10 full length cassettes of sound poetry is rare under normal circumstances. Curtains was a poetry (or poetry-adjacent) magazine edited by Paul Buck during the latter half of the 70s, a prominent publisher, among other things, of many French writers who were largely unknown to English-speaking audiences at the time. It also pursued a holistic poetry-by-other-means program that naturally veered into recorded documents of performances following Buck’s interest in the written word’s oral tradition.

The audio arm of Curtains was short lived (owing to disruptions by prudish local press/harassment around Buck’s novel Lust, as well as an uncomfortable proximity to the Yorkshire Ripper murders), releasing only two tapes, which are reissued herein (Eric Mottram 1 and Paul Buck/Ulli McCarthy [now Freer] 2/3). The remaining seven of this box feature artists who were either set for an audio edition on Curtainsor who were close associates, contributors to the magazine, friends who sent private recordings to Buck etc. Taken as a whole this box set is a fascinating document of a fertile time in international experimental writing, where boundaries between the written, performed, musical etc. were being enthusiastically blurred and/or exploded. There is an incredible sense of motion both forward and back, as folk traditions are thrust into contemporary dialogues, and a disarming, organic quality throughout, many of the tapes being works in progress with all the digressions left intact. The straight reading pieces are often a bit dry for my liking, but there are plenty of highlights, be they McCarthy’s verbal counters to a loop of Satie’s “Gymnopédies”, Kathy Acker’s reading and commentary on censorship from a public access radio interview, or Buck’s own studies merging compositional methods as diverse as the aboriginal sounds of Arnhem Land, Inuits of the Arctic, the shrieking theatre of Artaud and the extended technique of Joan La Barbara.

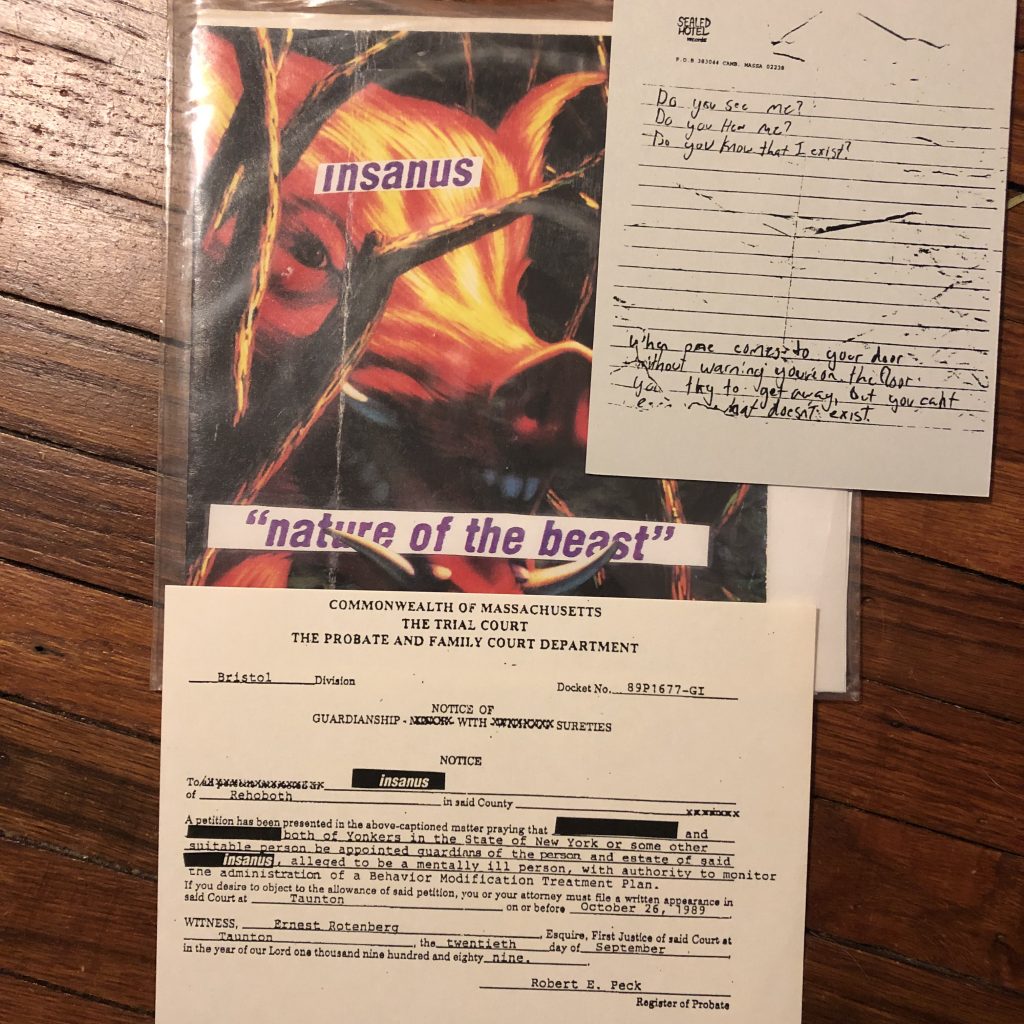

And we wrap up proceedings, fittingly, with the stupidest thing I heard all year, once again via recommendation, this time coming from the esteemed head of Fusetron, Chris Freeman (well, to be fair he never said I should actually buy it).. The record in question is “Nature of the Beast” by Insanus, a justifiably obscure one-off bargain bin EP reportedly recorded in a Rhode Island mental hospital, though the back cover photos of pay stubs from a local McDonald’s suggest whoever is responsible for this curious entry to the outsider metal canon was in on their own joke. It came up initially in a discussion of the “shockingly shitty sounding” Reji Cat Jimz’s Christ Straight From Hell, an LP that’s been on my want list for some time. While the latter has been likened to an unholy marriage of Vulcan, Dwarr and The Shaggs recorded straight to walkman, I’d say Insanus lowers these already modest stakes to a Jerry Rayson-fronted Afterbirth. Was it an oversight, or deemed too asinine for even the Shit List? Sounds like they’re having fun at least, and with a price tag well below double digits, there’s plenty left over for a McRib if you ever find yourself in Warwick. Consider it a contribution towards the Green New Deal (better rotting away in your 7″ box than a landfill).

/////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

Do you record marginal music to keep yourself from going insane? Would you like for it to be reviewed? If so, e-mail crisisoftaste [AT] gmail.com. Only physical releases will be considered, and reviewer reserves the right to discard upon unsatisfactory listening experience, but if what you send is good then that shouldn’t be a problem.

Follow

Follow