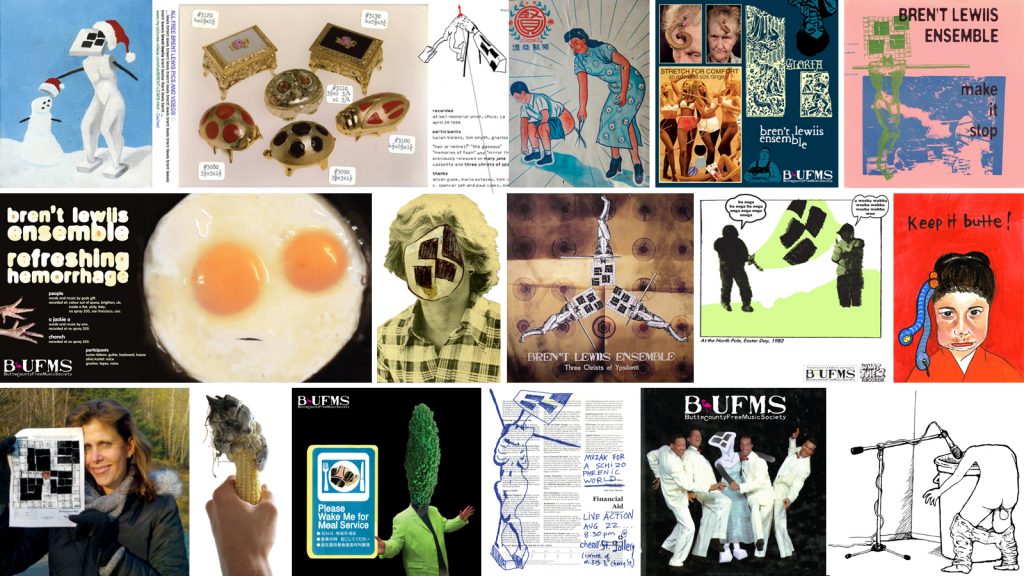

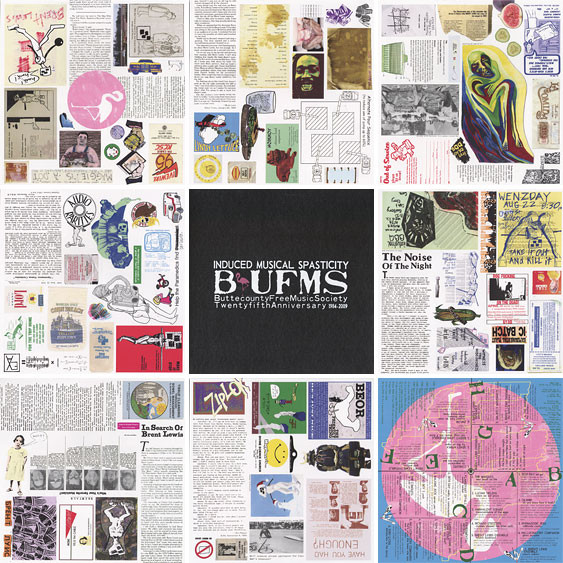

Seymour Glass is a weird music lifer who requires no introduction. Many first came into contact with him via the seminal Bananafish magazine, a venerable institution of strange audio (and other) activity he edited from around 1986-2004 (an excellent interview chronicling this time can be heard here). In the years since the final issue of Bananafish was published Seymour has, in addition to running the Tedium House distro, been extremely active alongside a close group of friends under the umbrella of the Butte County Free Music Society. Their work was first documented on the brilliant Induced Musical Spasticity archival box set issued in 2009, featuring recordings made in and around California State College during the early 80s. This was followed by a steady stream of vinyl and CD releases of more archival works by the likes of The Conduits, Vomit Launch and Maria Estevez, as well as plenty of new material from BuFMS flapships Glands of External Secretion and Bren’t Lewiis Ensemble. I was curious to hear about the history of this uncanny collective, so I hit Seymour up and he delivered the goods (and then some). Redeem your T.V. cheese voucher below:

_________________________________________________________________________

Mutually Assured Marginality: All right let’s get the boring standard opener out of the way: Formative artistic experiences? You grew up in a culturally bereft area of Connecticut and moved to Northern California as a teenager if I’m not mistaken. I know you’ve mentioned a Caroliner gig around this time leaving a big impression, as well as stuff like Throbbing Gristle, “Cartridge Music” etc., but can you recall, even from an earlier age, what spurred an interest in things that were a little off the beaten path? To what degree did general curiosity mixed with the tedium of small town U.S. life play a role?

Seymour Glass: I should probably walk back the characterization of my hometown as being “culturally bereft” a bit…

MAM: OK, that was an assumption on my part. I was going off of previous interviews, I think you mentioned the only place to find records there was the library and an audio repair shop? And the culture shock experienced when you moved to the Bay Area and there were cheap records everywhere?

SG: I’ve definitely contributed to that perception. But the public library that I’ve referred to was great. I loved going there. And our houses were filled with books. There were two different painters that my family knew personally, one of whom I sat for when she was teaching classes. The other guy, his name was William Cudahy, he’s fairly well known for large oil paintings that were kind of Expressionistic, almost Abstract, big blats of color of beautiful landscapes. And the town where I lived, New Haven is a half hour away, it’s about two hours in either direction to Boston and New York. The feelings of isolation and “it’s so boring here” would have dissipated in due time, once I felt comfortable. New York City was legendary at the time for how hellish it was; as a kid in the suburbs I was terrified of it, but it’s not impossible to think I could’ve made it there on my own and done all the things in the late ’70s people talk about, going to see shows at loft parties and all that No New York stuff. I’d have taken my clothes off if Andy Warhol told me to.

MAM: When exactly did you move to San Francisco? Or I guess you lived in Chico first?

SG: We moved to the Bay Area in ’78, and about a year and half later I went to college in Chico. Part of the reason we did that was because it was so cheap. Tuition was almost non-existent then, it was the tail end of that era. Even while I was in school the amount of grants and loans available to me was starting to decrease, but by then I’d been there long enough to kind of figure out the system and how to survive with less money and get part time jobs to supplement the income.

So this small town, Madison, Connecticut — it’s not a secret —is socially conservative, from what I remember, which is typical of New England. The last time I was there, maybe ten years ago for a family gathering, I was put in charge of the daily acquisition of wine. They know if they give me $150 and tell me to go get wine, I was not gonna blow it and come back with change. I went to the one wine shop in town, cash-in-hand, and tried to ingratiate myself ever so slightly with the guy behind the counter. “I want a reds, whites, something from France, something from Italy, something from Sonoma County, and you pick something that nobody knows about.” I would do this everyday, and there was just no glimmer of recognition when I walked in, no “Hey, how was that Argentinean Beaujolais I turned you onto?” It was just “Hi, may I help you?” The look on his face was like “Is this guy gonna rob us? Is he gonna urinate on the floor? Beat me up because real men drink Pabst Blue Ribbon?” Everyday for a week! [laughs]

Anyway the things that got me into left field music… It happened very gradually. At some point, like when someone asks, you look back and piece things together. I wasn’t born thinking, “Ya know Xenakis is the greatest composer who ever lived.” I didn’t start collecting everything on the Nurse With Wound list in anticipation of impressing someone I’ll never meet.

MAM: Oh sure. Was it more so like Frank Zappa, Beefheart, or reading Rolling Stone or whatever you could get your hands on?

SG: Reading Rolling Stone for sure, that was one of the things they had at the library, but in combination to reading it was not being able to hear much of what they were talking about. But even before that, I think it’s the same for a lot of people, as a kid, the visual element is most important. I watched a lot of cartoons. Single parent home, gotta rely on the electronic babysitter. Bugs Bunny had music by Carl Stalling that followed the on-screen action and antics of the characters, and not traditional rules of musical theory. A bunch of the material has been released on CD, and it’s quite easy to hear how odd it sounds without the pictures, but at the time, it didn’t feel unnatural or peculiar. Looking back, I would say the seeds were planted here.

MAM: And a lot of that is pretty evident, you can definitely hear that in your own music. That sort of kitsch-y novelty aspect. Though in more of a perverted form.

SG: Sure, I wouldn’t deny it. But there was more to it. The Beatles had their own cartoon, so did the Jackson 5 and The Osmonds. Rock music was everywhere and it was available to people of all ages. My mother had records by The Animals and The Kinks and The Rolling Stones and The Beatles, and here they were also on TV.

One drug store in town had a really nice magazine selection, a classic small town drug store, not like a CVS or Walgreens but with a counter where you could get a grilled cheese, a milkshake, and lemon meringue pie, a little snack while your prescriptions are getting filled. I would look at Mad and National Lampoon and, of course, there’d always be some crabby old man who, the minute you walked in, was on top of you because “Reading is stealing” and “We’re not a library, you have to buy that!” And it’s like “OK, can I just make sure I don’t own it already, fuck! It’s $1.25, relax.” [laughs] But they had Hit Parader and I think they had Creem, too, and those both tended to be a little more provocative with the visuals. Rolling Stone was more political and concerned with ‘serious cultural criticism’, but these guys were more decadent. So you could see low angle crotch shots of The Tubes with actual pubes sticking out among the glitter, Roxy Music and The Sweet, and I’m sure I’ve mentioned the cover of They Only Come Out At Night by the Edgar Winter Group before. So I was encountering things like androgyny and gender-bending here and there I think because it was easy to get it into magazines. You wouldn’t see other transgressive shit like William Burroughs in a mainstream magazine in the rack at the drugstore, but you could see saucy guys dressing kinda weird. And being a teenager, I noticed anything having to do with sex. That is what led to this realization that there’s a world out there filled with things I’d never experienced. I didn’t know anybody who looked like that. “Who acts like this! What does their music sound like? Who are these people?”

But then sonically, there were bits and pieces of standard mainstream Rock music that were pretty weird. A classic example would be the middle part of “Whole Lotta Love,” the song comes to a grinding halt, and becomes an echo chamber, a little bit of hi-hat and Robert Plant having an orgasm out in the woods or something. You could hear that on the radio all the time. Same with Dark Side of the Moon. I can’t even listen to that anymore, now it just sounds like Billy Joel to me. I probably listened to that record twice a day for a year, it was my favorite record as a teenager.

MAM: Did you work your way backwards at the time, not even to the Syd Barrett stuff but just the pre-radio mega hits with some of the more experimental production and jamming?

SG: Yeah, an album like Ummagumma — double LP for the price of a single album, you gotta get that, it’s a bargain. The live version of “Astronomy Domine” on there, the melody was quite disturbing at first, “Blegahh, blurrghhh…,” so horrible sounding, but I kept going back to it, trying to figure out why it sounded so scary and messed up. My uncle Andy gave me his copy of Freak Out! by the Mothers of Invention with songs on there like “Who Are the Brain Police?” and “Motherly Love,” again with the dirge-y chord progressions, almost sounding out of tune, maybe they were out of tune, I don’t know. At the time it was like, “Oh my god this is so harsh and fucked up!”

Even late-era Beatles records had lots of studio effects and loops and voices I couldn’t identify. Lou Reed’s “Walk On The Wild Side” was a radio staple for decades — lyrically bohemian; musically, meh. But, that’s how I found out about The Velvet Underground. Another example is the first track on Queen’s A Night At The Opera, which is peppered with flourishes between the lines, between the verses, backwards sounds and weird clicking. The double-live album by Deep Purple, or Brain Salad Surgery by Emerson Lake & Palmer, they had these sections with just electronics going nuts. Chicago, another band you’d never think of in this context, one of their early albums has a track called “Free Form Guitar” and that’s all it is [laughs], just a solo track with the guitarist of Chicago going off like Jerry Garcia.

MAM: Were you particularly honed in to those freak out sections?

SG: Not at first. I was interested in all Rock music. I used to listen to WPLR in New Haven with a notebook, and I would write down every song they played. I was immersed in the whole world, I liked everything. From Loggins & Messina to Foghat… J Geils band… I didn’t care. After a while I developed my taste and realized I liked the things that are more or less ‘non-musical’ and all that stuff that happens in the intros and outros, where there’ll be a dramatic build up or the players improvise for a while knowing it’s not important, just for the fade-out, and will likely be thrown away. So you get an album like Freak Out! where it seemed like a whole album of songs made out of those things. It doesn’t always resolve, it’s not always harmonious, it doesn’t always release the tension, sometimes it jumps from one thing to another and then back again much later on.

I realized I was into Rock music more than most people in sixth grade. That was just a generally terrifying time. I had to go to a different school that was far away, couldn’t walk home anymore. That was the first year students were assigned lockers — a totally nerve-wracking development. I knew I was gonna be the first one to forget my combination and it was gonna be humiliating. You had to start taking off your clothes for PE that year, and I would have been more freaked out about having to shower with other boys if there weren’t other kids in the class who were absolute basket cases about it. “OK, they’ve got bigger problems than me.” [laughs] But the thing that happened that year was a music appreciation class, and we learned about ’50s Rock’n’Roll, everybody you’ve heard a million times, Bill Haley and the Comets, Elvis, Little Richard, on and on. I first I thought, “Oh, maybe this won’t be so bad after all.” The teacher would play songs and ask “Who is this?” and every time my hand was up. Or “What’s the lead instrument in this? What does the leader of the band play?” We’d take quizzes and I’d ace them. I was the first one done. I wasn’t strutting around like I was something special because of it, though. No one was impressed. Their attitude about music appreciation class was “Oh god, this again.” Even though I couldn’t help thinking, “What are you guys talking about? You’d rather be in the other classroom doing math? This is better than recess and lunch combined!” I wasn’t about to try to change anybody’s mind. I guess I had a natural motivation to be interested in it, whereas to my friends, rock music was just another element of popular entertainment that was paid attention to casually at best.

MAM: But that’s music appreciation which is different than theory or…

SG: The class might have gotten into theory later on, and was starting off with ’50s rock’n’roll just to ease us in to it. I got transferred to a different learning track that year, and those students took chorus instead of music appreciation. Which I hated.

MAM: Did you ever learn to play an instrument? You were more a fan of music rather than wanting to make your own at this point?

SG: I wasn’t really into creating it, or learning how to create it. I don’t remember exactly, but maybe there was a stigma associated with playing an instrument in school? Allowing my fears to hold me back is definitely something that I’ve done a lot in my life, especially when I was young.

All the stuff that I now know how to do came from trial and error, both on my own and with others, or asking people who know what they’re doing how they did it. Or reading about pioneers of the genre. The first attempts were just playing with my sister. We used to play “Mission Impossible” with each other. We’d leave each other messages on a reel-to-reel tape recorder and place it on top of the front tire of my mother’s car. But the whole figuring out how to cut and splice tape, that came later when I was working at the radio station in college, putting together commercials and stuff. That’s how I learned the technical aspect and eventually that I can do it with whatever I wanted. It doesn’t have to be about selling ice cream cones at the local parlor.

MAM: So you were doing that stuff in college with the radio engineering, which is around when Bren’t Lewiis Ensemble was getting started as well. Was that basically the first time you’d ever played in a sort of proper band? I know you sang in a Rock band as well, I’m not sure of the timeline on that…but was this the first stuff that was more improv or…I guess a lot of it was almost performance art, the stuff that ended up on the boxset [Induced Musical Spasticity]. How did that come about?

SG: The radio station, KCSC, was instrumental. That’s how a lot of us met, how a lot of us got comfortable with each other and the equipment. And it also broadened our knowledge. It was a great meeting place for people to turn each other on to different kinds of music. We had contact with people who were real musicians who were writing songs, practicing them, getting to the point where they were proficient enough to ask people for money to entertain them. We were familiar with that concept, but we didn’t have any of the training necessary. Though we knew of various ideas about other ways to do it, from John Cage to music therapy classes for children. From the hi-brow to the lo-brow, it was all there ready for us to connect the dots. And there was a lot of pot-smoking, of course. There was plenty of shaking the spray canister and listening to the little ball rattle, putting it up to the mic and running in through the Fender amp, “Listen to that reverb, man!” [laughs] That was a big part of it too, just goofing around…

MAM: But you did record a lot of stuff and eventually played live on campus and everything, and had a bit of a following…

SG: And our eye-rolling detractors, too. This was the first half of the ’80s, I think we played maybe half a dozen times…

MAM: And it was you and Lucian… were you two sort of the core and then you brought in others as needed for performances? Did you conceive of it as a formal group, a band, or was it more open membership?

SG: A little of both, but also neither. We didn’t make any hard and fast rules. As far as we were concerned everyone was in Bren’t Lewiis, whether they knew it or not. One of the things we’d picked up from Industrial music was the sound of machines doing what they do — that’s music, and you can imitate it, try to play in the style of a printing press or something, or you can record the actual printing press and incorporate it into what you’re doing. The notion of found art or field recordings, the fucked-up car with a hole in the muffler, the idea can be extended to people. There was definitely a big circle of friends, people we liked, who if they were willing to do something with us then, sure, they were in the band. For that moment, at least. There was no gatekeeping. Sometimes it would be five of us, sometimes more, rarely the same combination. People came and went, but Lucian and I were definitely the two that were the most into it. Probably because we were the closest as friends. That’s what holds it together.

MAM: Did you know each other before college?

SG: No, a woman named Toni Smith who worked at the radio station introduced us. She’s kind of responsible for the trajectory that a lot of us went on. She was in a class with Lucian and she knew me via KCSC.

MAM: What kind of stuff did you play on your shows? Was it pretty relaxed in terms of what was allowed?

SG: It was a cable radio station (now it’s Internet radio), so it wasn’t so strict about things like on-air swearing. The only way you could hear the station was to hook up your cable to the receiver, you were paying for it, so there wasn’t that need for “protecting the public” that more accessible stations had. The station had a general format and conventions. Albums were in different categories, which was the purview of the music director, and DJs were supposed to play things from each category with some consistency. A standard by which few of us abided.

I was one of three hosts of the punk and hardcore show. I also did one that was more or less what you’d hear now on a BuFMS disc, but more inept. I would get people from the various writing classes I was taking to read their work. We could pre-record them and add sound effects and other music, or if they were willing to stay up late and come to the station from midnight to 2am on Thursdays, they could do it live. There would come a point in the show when all the mics were on, and if you were there and wanted to, you could grab something from the box of papers and manuscripts and books in the studio. This was a practice many of us incorporated into our shows, I wasn’t the only one. Anyway, I’d play records as well, but people reading their work was a big part. It definitely helped with this idea of working together with other people, taking their raw material and trying to figure out what to do with it. How to collaborate on an equal level.

MAM: Yeah that’s a good segue to something I wanted to talk about, which is how BuFMS all came together. I know it was sort of after-the-fact, you didn’t call it that at the time, but when you were doing all this stuff did you think of it as an amorphous collective project? Like were LAFMS and Smegma in your head in the early 80s, or was it all attributed later when you put together the box set?

SG: I found out about LAFMS around that period, and it helped me a lot. It was the Pigs For Lepers cover… I’d never heard of them but a raw chicken with a baby head on the cover. I was all, “What the fuck? There is no way this record sucks, and even if it does, I’ll have something for the wall.” [laughs] So I brought it up to the register, it’s like $2…

MAM: Jeez, yeah, think I paid a little bit more for my copy 30 years later! [laughs]

SG: Even the cashier said, “I was wondering who was gonna buy this. We have this cassette compilation on the wall by the same people, it’s also $2.” And it’s the Light Bulb – The Emergency Cassette compilation, two 60 minute tapes. Both of them are unpredictable and sound like everyone is having fun. At the time there was no pretense on our part that we were an organized collective. It was just a bunch of people doing whatever they wanted.

MAM: And you released some things on cassette, very limited quantities.

SG: Yeah, just dubbing them for whoever wanted one. I’d just take blank tapes from the radio station. I liked the fact that LAFMS was a collective, but it wasn’t more important than liking what they were doing. If I didn’t like it, the collectivity aspect wouldn’t change my mind, and if it wasn’t a collective, it wouldn’t make me like what they were doing any less. But I still like the group aspect, and as far as the credits on our stuff, part of the reason I don’t list out who does what is practicality, the recording sessions are chaotic…

MAM: Oh yeah, it’s not always clear who’s doing what?

SG: Right, you couldn’t keep track, everyone’s doing a million different things. Plus, I’m editing it all to hell and back later. But if we did decide to list everything specifically, I wouldn’t be against it. I just don’t want to be the one who has to figure it out.

And then the other thing is maybe a little more philosophical. We’re all connected via our friendships, personalities. Speaking personally, the confidence I have in expressing myself comes in large part from having this group of friends for such a long time who I know are going to be with me. And why I gravitated toward the people I did, that goes back to being a kid and listening to my relatives banter and yack about stuff. They were hilarious, they’d go on for hours. I didn’t know what they were talking about but I would just listen. We’re not composers or conductors, though we tried a few times. Tim Smyth compose a piece called “Gloria,” it was a theater piece and a tape piece. Props, roles, costumes… We never got around to doing it, which shows how successful we are at that sort of thing. But none of our ideas exist in a vacuum. Everything bounces off everybody, every thought or action, you might not have done it that way if you were by yourself. The aggregate sensibility was built by all of us together over a period of time. So collective authorship, I think, is easier and feels better for philosophical reasons. And then there’s just garden variety sentimentality, these are my oldest, most cherished friends, so that’s how we’re gonna do it.

MAM: Alright, so you mentioned that LAFMS material having a sense of “unpredictability” that you found appealing, which reminds me of something you’ve said about Bananafish, that the goal was for the reader to not be able to tell what was coming on the next page. The same could be said for a lot of your music, I think, but not in the way I associate with improv. Is that something you tend to have in mind while recording, trying to create that kind of atmosphere or feeling where one doesn’t know what to expect?

SG: Sure, but as far as how the recordings are made, most of them are improvised. Even if I’m bringing pre-recorded stuff to play during the session, it’s done without a preconceived idea of exactly how it’ll happen. When everyone else is playing they don’t know what the final form will be. We all understand that everything is raw material. Sometimes it remains exactly as it was performed, but even when I’m mixing and editing an album, at the 11th hour I might decide to redo things, combine tracks or rip them in half. With the editing there’s a lot of improvisation as well. Some days I just feel like a track should have a lonely, desolate vibe, so I go with low volumes and nothing that jumps. Whereas another other piece will be more diverse with shorter elements and channel-jumping. You’ve got to find that sweet spot where you’re not being self-consciously quirky, almost random-sounding.

MAM: That’s something that definitely strikes me about it, it does walk that line, where it’s unpredictable but it also tends to feel intentional. I guess that’s why it doesn’t come off as totally free form to me. Especially with all the spoken word elements, and maybe your background in writing is relevant to this end?

SG: In all aspects, words are pretty essential, and that extends to everyone in the group. Words are one of the most important things, even if you can’t hear them in the track. Sometimes we grunt and moan, or we write gibberish and perform it, sometimes the gibberish just comes out. Tom Chimpson regularly makes us watch movies and videos before we record or perform, so even if it’s not directly part of the show we all have it in our heads. It can be anything, old cheeseball movies… Flash Gordon or something… or old videos from Top of the Pops, we’ll be pissing ourselves about somebody in the Moody Blues with helmet hair and then we go out with that in the back of our minds. One thing I’ve been doing a lot lately is lyrical mashups, combining like the lyrics from a Led Zeppelin song with text from a John Steinbeck novel, that’s on a track called “Substratum Dream Of A Flag Pole Sitter.” Or combining the lyrics from a Christina Aguilera and a Flipper song, an old song by France Gall with dialogue from a Woody Allen movie, that sort of thing. The lyrics of “Five To One” by The Doors is from the perspective of youth in revolt, “we’re coming for you, old man…” You know, just the vibe of the ’60s when the youth were coming of age and they far outnumbered everyone and were gonna take over. So we rewrote that from the perspective of the people in the castle under siege, “Yes, our ballroom days are over, it’s all coming to an end,” and then we mixed that with a song by the New York Dolls, which is itself a cover of an old 50s tune, “Stranded In The Jungle,” where this singer realizes cannibals are trying to eat him and he hitches a ride back to the States. In the rewrite he’s racing across the ocean to get to the President to tell him that the revolution is coming.

And some people have distinctive voices. Lindy Lettuce has this beautiful baritone; he could do that “we have the meat” thing for Arby’s commercials. Joan of Art is tiny but loud as hell but can also do a magnificent wasted slur, like a monarch on the verge of losing consciousness. Lucian is exceptional at characters. Then there’s The Red Dragonfly and Silvia Kastel, who have non-American accents. Even before you get to the content, there’s all these people who you want to hear from.

MAM: So as you go about your day you’re constantly looking for odd phrases?

SG: “My Down Booties Were Eaten By Pat’s Dog” was one of the first ones. It came up in conversation, believe it or not. Amoeba Man said that and it just sounded so odd, so we kept repeating it over and over and it became this kind of hypnotic mantra. One of the more recent ones, “My Mother Wouldn’t Let Us Use Nicknames When We Were Kids,” I overheard someone say in line at the grocery store. We usually do them the same way: everybody says it over and over again; how they overlap, how they are said, or how long it lasts is up for grabs. I wouldn’t say we look for them, but rather that we remain open to their discovery.

Tom Chimpson regularly writes things with the idea that multiple people will read them at a recording session and we’ll see what works best later on. And then sometimes we read things straight out of books. On our most recent CD Lucian read from 117 Days Adrift, about a couple stranded on a raft who catch a sea turtle so they can kill and eat it. I’ve read from Gravity’s Rainbow, Lucian’s read liner notes from an album by Orion. There’s a thing about Diego Rivera engaging in cannibalism…

MAM: That seems to be a theme! [laughs]

SG: We all share is an interest in what is far afield from everyday experience. Tom Chimpson is a good idea man, and like me he shows up to recording sessions organized. Not necessarily with a plan, but with a lot of different possibilities.

MAM: Maybe this is a good time to talk about specific people and what their roles are.

SG: Sure. Tom Chimpson has a nice voice, kind of neutral but I find it quite soothing. He likes children’s stuff so he’ll find lyrics from a song on a cartoon from when we were kids, but when we appropriate it, there’s an added layer of surreality. We just did “Go Tell Aunt Rhody” on a recent album, that was his idea. He also read selected sentences from a radical newspaper and you’d never guess the source. Now it’s about about insurance and seaweed. Sometimes he focuses on clusters of words, or elongates vowels into continuous tones. You never really know. He messes with things in real time. He found a novel called The Disciple by an English professor we all had in the ’80s who’s since passed away. None of us had ever seen it before, or I don’t remember seeing it, at any rate. He recorded his favorite passages at our most recent recording session, and the idea is for all of us to take the book for a while and record what we like. That’s a long-term project. But the putting together of sentences to make a new different story, that’s something we do with thrift store cassettes. All these different voices speaking obliquely about presumably the same topic, although at the time they weren’t. You end up with this story that you didn’t write, that no one really wrote, but it sort of fits together and is more puzzling than anything.

MAM: Sort of an Automatic Writing type of thing?

SG: Yeah. Well, almost the flip of that. Not so much stream of consciousness, moments where the multiple consciousnesses are streamed and intersect. Starting at the end and working backward. That’s why I’d say it’s a mix of improvisation and planned elements. Words are important to all of us, and Tom is someone who…

MAM: This is a real person, right? Because there are lots of pseudonyms involved.

SG: Oh yeah, Tom is a real person. Lucian’s name regularly gets pronounced by people as if it’s spelled “Lucien,” so we sometimes refer to him in writing as “Lucy N.,” to mimic the pronunciation. But that has no effect on his existence as a person. Barbara Manning is another member of the group. Bona fide songwriter par excellence.

MAM: Oh yeah, of course, I’m a fan. And she doesn’t like the kind of music you guys do exactly? You mentioned in the Daniel Spicer interview she refers to it as “scary music”?

SG: It sounds like what you’d hear in a horror movie, and she’s right about that. The supernatural, the paranormal. She makes that connection because she’s a real musician. Chords and notes and melodies have meaning to her, she can make a chord that expresses “melancholy” or “longing” or “optimism,” and we can’t really do that. It just comes out however it comes out. And a lot of times, we use things that are backwards or played at the wrong speed, pitched up and down at the same time. I get why she calls it scary. When she decides that she’s gonna play on something, she has to tamp down all of her training, she has to work harder to bang around on stuff than we do. When she commits to it, though, she’s excellent because she has a great ear. She can listen and react really fast and she knows how to do counterpoint, or call-and-response, all sorts of musical tricks. When we played in Los Molinos, at Double Happiness in Joan Of Art and Asskicker Bob’s garage, she has a mono Korg synthesizer that she bought the same day as the show. She just opened it up, figured out how it worked and then played it a few hours later, and you would never know.

Lindy Lettuce I’ve already mentioned, with that beautiful baritone voice. He’s very blasé about things, like he could give a shit about any of it. If I had my own TV or radio station he would never want for voiceover work. You know that movie The Big Lebowski, the cowboy character that pops in and talks to The Dude in a low voice?

MAM: Sure.

SG: When Lindy was trying to get legit freelance voice over work, he constantly lost the job to that guy. He hates him! [laughs]

The City Councilman is our resident gearhead and has been working for a couple years with the people at MusicLandria, an instrument library in Sacramento. You never know what effect boxes or synthesizers he’s going to have at a recording session. He also films and edits all of the videos that we make. At first it was two freeform elements happening at the same time. It was easy, almost impossible to fuck up. Then we got to the point where he would tailor the video as much as possible to the audio. Right before the pandemic started, we were moving toward recording audio to videos that he made first. That’s something I’m looking forward to continuing once we’re allowed to go outside and breathe each other’s air again.

Maria Estevez, back in the college days, was quite essential. She recorded a lot of sessions. Now she’s fairly well off and an important person in her profession. She’s a bit like, “I don’t want anything to do with you and your art projects any more.” [laughs] She’s nice about it, and I did convince her to let me release the soundtrack to the movie she made but there’s no way anyone will ever see the movie. She’s relaxed somewhat because she realized there’s no way a BuFMS CDR will intersect with her current world.

MAM: And outside of BuFMS, you do have close relationships with a few other artists, Dylan Nyoukis of course, and you and Andy Bolus have worked together a bit. Or even Tom Darksmth and Orchid Spangiafora, certain names crop up repeatedly. Obviously there’s some aesthetic similarities, is it just a case of liking each other’s work and getting on well or…what do you think accounts for those kinds of long standing artistic relationships?

SG: Liking people for who they are accounts for way more than liking their artwork, really. You can think of all sorts of people who have done amazing work, Phil Spector is a topical example.

MAM: Oh sure, lots of great artists are fucked up people.

SG: I have plenty of friends who I adore but are kind of aesthetically opposed, we don’t have much in common in that way. But yeah Dylan, he’s just hilarious and interesting, the sort of person I’ve gravitated toward since I was a little kid.

MAM: But it does seem like a US / UK mirror image, with the labels at least. Not that they are exactly the same. Chocolate Monk puts out lots of different artists, of course, whereas BuFMS is more a close group of friends, but it seems as an outsider that there’s an influence going both ways, bouncing ideas off each other similarly to what you said about the recording sessions for Bren’t Lewiis almost…

SG: Right, my inroad to the international experimental underground was the magazine, that’s how I met everybody, and he met everybody through the live shows, the festival [Colour Out Of Space] and the label. Andy I’ve known for about as long, but not nearly as well. The first time we even met was December 2019. When I did that Noisextra podcast, we met face to face within like ten minutes of that starting. They interviewed me first and I talked forever, and then they started with Andy but we had to leave, so they had to finish up later. But yeah his artwork has always fascinated me. It’s not one thing, sometimes he does painting, sometimes he paints over other people’s work…draws and rips things up…he has a whole comic book that he appears to have drawn but I’m not even sure what the method was. That’s kind of what fascinates me about anything, figuring out how it was made. Even like photographs of wildlife, sometimes the image is so clear, you can see the ornate textures and mix of colors on the the beak of a bird, you have to wonder if it’s real photograph or if it’s been messed with.

MAM: Yeah, trippy. Did psychedelics play a big role in forming your world view early on? Either from taking them or just there role in culture at large?

SG: They were probably the most prominent kind of mind-altering touchstone of my youth. They were very popular for people slightly older than me when I was a kid, and because of that they were visible in areas that were available to anyone, cartoons or fashion, for instance. But even humor and absurdity, there’s an element of that, a more general kind of “mind altering” happens when you encounter something that doesn’t make sense at first, and maybe you realize it’s not supposed to. Like the paintings of Magritte, a room with this enormous apple in it, or a guy with an apple floating in front of his face — they’re arresting, they capture the attention. Even just reading a book, that’s mind-altering. Using your imagination, trying to figure things out, those are forms of mind-alteration. Doing mushrooms, acid, even smoking pot or getting drunk, they obviously alter your mind, too, but it’s temporary. I did some writing under the influence of mushrooms, enough times where I could remember the frame of mind I was in, and could start to see the associations I was making and then do it sober.

MAM: Some people say Krautrock, for instance, only lasted a few years because so many of the artists were just bombed out on acid. I do think about experiencing it at the time, you’re 20 years old in Cologne in 1971, or SF in ’67 obviously, you must be thinking “This is gonna change the fucking world! Everyone is gonna be tripping and making music all the time!” and then six months later half your friends have literally destroyed their minds and can no longer function. Patrick Lundborg talks about this in Psychedelia actually, how with all the social unrest of the late 60s, Vietnam and the assassinations and everything, it was a very inopportune time for psychedelic drugs to come into the wider consciousness. Anyway, a PSA for all the youth…

SG: Trip responsively, kids!

MAM: Set and setting, very important. OK, the last thing I wanted to ask about was the BuFMS book, which I guess was initially going to be an article for As Loud As Possible. That article sprawled out into a whole book documenting the history of the collective that is in the works; can you talk about that at all?

SG: The title is Sputtering and Distorted: An Oral History of the Butte County Free Music Society and the jumping off point is the artwork that’s inside the box set Induced Musical Spasticity. But it goes into films, fanzines, theater stuff, stand-up comedy, TV shows, all sorts of things that people were doing, related and not related, before, during and after the time period of the box set, the early ’80s. It’s not intended to be definitive or exhaustive, just a bunch of people talking about what they did at the time.

MAM: Who’s writing it?

SG: An old friend of mine, Fen Addison, is doing a lot of it, just so I don’t have to write about myself too much. [laughs] But I’m looking over his shoulder, editing it, and writing a bunch of it, too. He wrote something for Bananafish once, a guest editorial. I don’t know if you remember but after 9/11 when Stockhausen was quoted saying something regrettable…

MAM: He called it the “greatest work of art in human history” or something like that?

SG: Yeah, and people were ready to lynch him, people who’d never even heard of Stockhausen or cared abut anything he had to say before that. Didn’t matter that what he was talking about was metaphorical, it was taken out of context and it was in German. They were still mad even though it wasn’t really anything.

MAM: Good thing that never happens anymore! [laughs]

SG: Yeah, really. So Fen wrote an editorial sort of in defense… not so much of Stockhausen, but more a “fuck you” to all the people who were pissed about something they didn’t even understand. It may have had something to do with that Cornelius Cardew thing as well, “Stockhausen Serves Imperialism,” I think it’s called?

MAM: Yeah that’s a book, or maybe it was a pamphlet, he wrote in the ’70s I think.

SG: Yes. The editorial was called “Stockhausen Serves Terrorism.” [laughs] Anyway, he’s been helping with the book and last time we did a word count it was around 95,000, and I estimated it’ll be around 200 pages, but I’m not really sure yet. We’re not set on the design. There will be a lot of artwork to go with it, which obviously determines how many pages it takes up. So we’re working right now on what we’re calling “the brutal edit.” If we don’t have all the details, then don’t mention the details. If we can’t confirm the spelling of someone’s name, then don’t mention them. If we have no graphic, then we don’t have one. We’re trying to plow through it and get it done by the end of the year.

MAM: But it was originally gonna be an article for that magazine, which is unfortunately no longer functioning, last I heard. When did you decide to make it a whole book?

SG: I think the editors, Chris Sienko and Steve Underwood, were imagining I’d go through each bit of artwork in the box set and give a sentence or two about each thing, but it turned out that explaining why there’s a pair of nose hair clippers shown, first there’s the person who was concerned about hair in his nose and was always teased about it. Then there are the things he did and said, and with whom, and on a related note, and one thing you should know, oh and about the guy he did that one thing with… It got out of hand immediately. A nightmare for them to publish. I’m thinking we’ll have to do a Go Fund Me, to manage our preorders.

MAM: Hey, sign me up, I’ll donate!

SG: We’ll have a lot of premiums as well. “You want a Star Trek Blu-ray for ordering early? You got it.” Weird cookbooks and toys, it will definitely be within character.

MAM: Any other upcoming releases?

SG: I’d like to do another volume of Lawrence Crane’s solo work. He’s a producer now, and has a magazine called Tape Op. He was in Vomit Launch, one of the most organized people I’ve ever met. He’s the guy who got me into tape trading. I knew how to play the game from working at the radio station, you’d send your playlists to record companies in order to get new records, but tape trading was different. These guys are going to answer you, and the answer is “yes,” and they will send you their tapes and art and objects. It’s so much easier, you get weirder music from more engaged people.

I was also in a group that didn’t last long with Greg Freemen, bass player for Pell Mell, record producer, and Scud Mandrill from a band called The Whitefronts. There were upwards of five or six other people in the group, all of them either in or connected to The Whitefronts. Each time we got together there were fewer and fewer people, until it was just Scud and me and his washing machine at the final recording session. I’m in the process of listening to those recordings to see if there’s anything I want to release.

There’s Bren’t Lewiis album in the works right now, the working title is Toupée Made Of Weather.

MAM: [laughs] We could spend 15 minutes on album and track titles I’m sure.

SG: And again that’s how verbal or word-oriented we all are. Lucian is constantly emailing me things, I add them to the master list and when the time comes we pick out what to call it.

I also did a lot of collaborations in 2020. Bryan Day, who is an instrument builder, Anla Courtis from Reynols, and Cody Brant. Those are all done, just waiting for the labels to put them out. The Cody Brant one will be on Chocolate Monk so that’ll be fairly quick, I’m sure. Dylan said “I haven’t listened to it yet but I’m sure it’s great.” I wonder if he’ll listen before he puts it out.

MAM: You should test him sometime. Just send him totally unlistenable garbage. 90 minutes of cats in heat…

SG: [laughs] Then when he gets mad, like “Why did I put out this Vietnamese pop music?” I can say, “That’ll teach you to listen to it first.”

I started a collaboration with Ali Robertson from Usurper, just the two of us, and then we also have plans to do a Bren’t Lewiis / Usurper collaboration but that’s gonna have to wait until the pandemic is over. I think everybody wants to be in person, or at least on their own side of the ocean when we make it. One aspect of what Bren’t Lewiis likes to do is all-objects recordings. Lucian and I can spend hours in a thrift store walking up and down every aisle, fucking with whatever we can get our hands on. And Usurper is low-decibel and focused, no effects, just objects on the table and their voices. I’m really looking forward to seeing if we can keep up with them. And I think you mentioned Regional Bears earlier?

MAM: Yeah, I was saying I interviewed Louis for this column a few months ago.

SG: His label is releasing a live set by Orchid Spangiafora and me. The recording of our Philly show that you and Jim [Strong] played at.

MAM: Oh cool. He did mention he was doing an OS release but I didn’t realize it was from that show.

SG: Feeding Tube is putting out an Orchid / Glands album that we worked on, not steadily, but off and on for about a year. And they’re also doing a lathe-cut LP of our set for QuaranTunes, from back in November. We played together via Zoom, which was hard, but it doesn’t sound as bad as I thought it would. Zoom is fine for two people talking to each other but playing live… We probably attempted it like ten times in the lead up to the show. You have to find a level where Zoom doesn’t mute either of you. But we each recorded ourselves at home separately, a direct line, and we just took those two recordings without the Zoom interaction, synced them up and that’s going to be on a lathe.

The Bren’t Lewiis website has more information, links, and whatnot. And I post regularly on The Butte County Free Music Society Facebook page about things we do and things we’re interested in but not necessarily connected to.

Follow

Follow